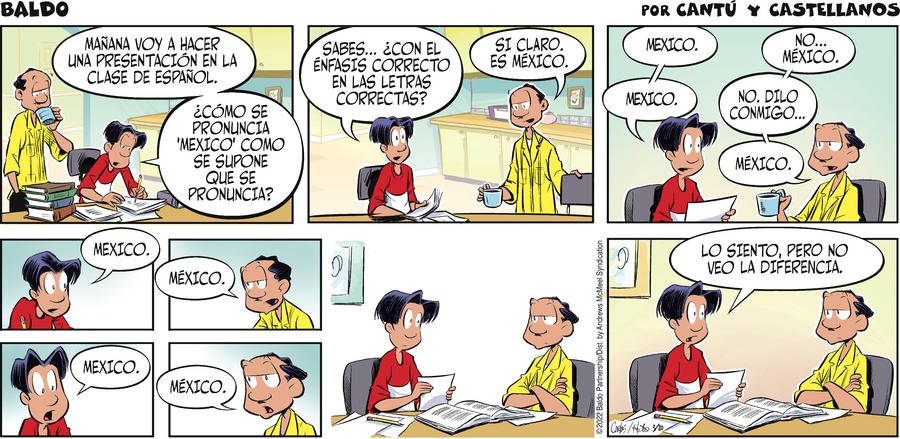

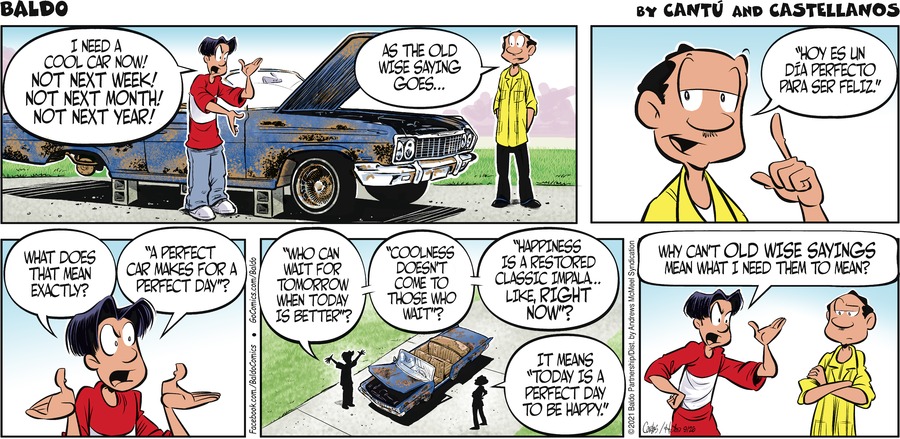

As we have asked before with Baldo, does the joke depend on language, and does it work in both the Spanish and the English versions of the strip?

Here there are two loci for our standard questions: In panel 2, the dialog from the second character (who I think must be Jake); and in panel 4, the second part of the dialog from the speaking character.

My take on those two, in short summary: The panel 2 pun works fine in English, and the Spanish also has something of a pun, by substituting a different statement instead of a translation. In panel 4, in the Spanish there seems to be an amusing equivocation, by virtue of a grammatical ambiguity; which does not carry over into English.

In some detail:

PANEL 2

In the English, notice the emphasis given in the lettering to the word TIRED. And while Jake says that, he is all over a stack of TIRES; even seemingly pointing to them as though in a sort of illustration.

In the Spanish, Jake’s line translates according to Google as “Oh, so you roll out of here early?” (and I think the “you” is not the only choice — it’s more of an impersonal, and might amount to “we”). So it no longer mentions tires or tiredness, but with the mention of rolling still manages to indirectly bring in the tires and roughly complete a pun. (And as a noun instead of verb, rueda is rendered first off as wheel.)

PANEL 4

OK, a bit of background. English (like, say, French) in simple sentences, in at least semi-formal speech or writing, requires an overt subject, even if a person and number could be inferred. Spanish (like many other European languages) allows skipping a subject pronoun if the verb form is enough to determine person and number. You can see this in both of Jake’s sentences in panel 3 — creo is 1st-person singular, but the sentence does not need to say yo creo; same for pienso not needing yo pienso.

Then in panel 4, the third character’s line Pero no creo que trabaje could be But I don’t think it works [it = the potential joke], or But I don’t think he works [he = Jake]. Which is a fairly good joke, or anyway language-amusement. [My point about not requiring overt subject pronoun turns out not crucial here, since if this sentence did use a subject pronoun, él for he or it would still be indeterminate.] But in English we get But I don’t think it works, and no secondary dig at lazy Jake.