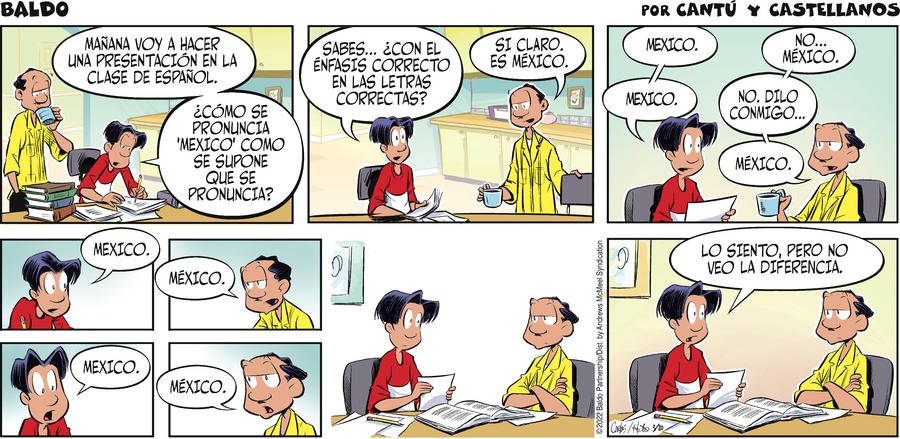

Thanks to Bill R, who says “It’s like they’re daring us to figure it out”. Which is why there is a CIDU category (“tag”) on this, along with the “(Not a CIDU)” for the OYs list in general. Look, don’t question it too hard. Oh, and it’s not a pun really, but gets an OY as a language-related item. Also this list was sitting bare too long …

The usage they’re disputing over was taught in my schooldays as one of “those common mistakes to be avoided”.

OK, I think (but am not positive) that I get the alternate meaning the joke depends on — from too many crime shows, the best deals a defendant’s lawyer might hope to extract from a prosecutor would involve setting no additional jail time, so the defendant gets to “walk away” or “take a walk”.

First I thought the outside guy was wearing an odd bathrobe; but throw in his laurel wreath and I guess he is at a toga party. But not the inside guy. Oh well, it doesn’t seem to affect the joke.

Possible cross-comic banter, based on spelling of the name?